Description

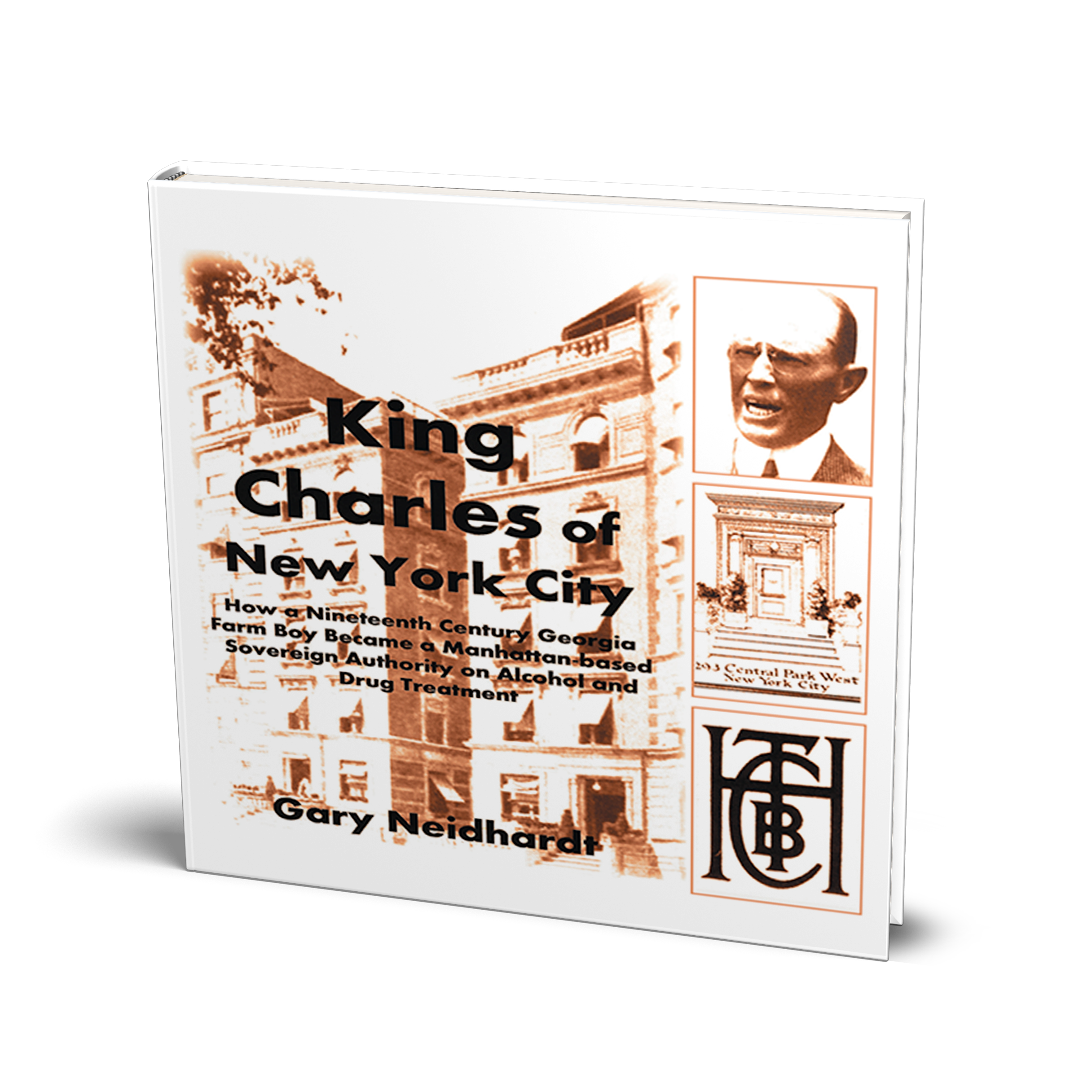

King Charles of New York City

by Gary W. Neidhardt

Westwood Books Publishing LLC

book review by Barbara Bamberger Scott

“Towns asserted so many alcoholics were ending up in mental institutions, jails and prisons because society did not know what else to do with them.”

The so-called “King” of New York City, Charles Barnes Towns rose from humble beginnings on a family farm. Although he had very little formal education, he eventually had virtual domination of a medical field most others had heretofore ignored—addiction. A little over a hundred years ago, “people could go to their local druggist to purchase as much morphine or opium as they could afford…” Medical journals contained ads for such products as Glyco-Heroin for everything from coughs to pneumonia. Around 1901, Towns, a former insurance salesman with no medical background but an astonishing gift of gab, announced he had a secret cure for addiction, opened a hospital in an upscale area of New York City, hired a respectable physician, and began to claim astonishingly high success rates for his techniques. He later disclosed that the remedy involved three medicinal (but poisonous) herbs combined with high doses of laxatives.

Towns’ book, Habits That Handicap, was reviewed in The New York Times; his numerous articles were read in the medical community, despite his giving no substantiation for statistics and other data. He went to China and swore he’d cured thousands of opium addicts. Decades ahead of science, he warned against cigarette smoking and the use of alcohol during pregnancy. The most famous of his patients was Bill Wilson, founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. Despite his atheism, Towns encouraged Wilson, whose faith in God came out of a vision he experienced while undergoing a cure at the Towns’ facility, and even provided financial support for Wilson’s book, which has arguably helped millions of alcoholics.

In his foreword, Neidhardt expresses the hope that this book will spur more interest in Towns. It is likely to do so, given the multi-layered, often contradictory personality of this unique individual as painted by the author—uneducated but brilliant, charismatic but secretive, greedy but capable of a great act of generosity. Truly, the activities of the “King” evoke more questions than answers. The author has drawn extensively from the limited stock of reliable information that surrounds this once high-profile figure. Neidhardt’s work obviously required fine attention to detail as is evidenced in the bibliography of Towns’ many writings, seven pages of references for further reading, more than 600 footnotes (many of them quite lengthy), and some vintage ads for medicines and the Towns clinic.

Neidhardt’s technique in creating this cohesive biography generally involves quoting from Towns or a contemporary then citing weaknesses or anomalies of his central character that come to light in the quotation. In so doing, he underscores the contrasts in this man who could be careless with the facts and yet prophetically visionary. For example, Towns was notably charitable in his modern-seeming assessment of many alcoholics as deserving not castigation but therapy and employment. Neidhardt’s most positive view of Towns comes to the fore when he shows how the avowed non-believer recognized the validity of Bill Wilson’s faith-based approach to alcohol dependence. Those who thoughtfully study Neidhardt’s examination of our national perceptions regarding drugs and addicts a century ago will almost certainly see parallels between those times and today and wonder what role “King” Charles Towns might play were he on the scene now.

RECOMMENDED by the US Review